After a very early morning discharge from the overnight train, we breakfasted and walked around the small town of Jambagly. Like Almaty, it is backed by spectacular peaks, but unlike Almaty it is peaceful and rural. Apple trees are common in gardens and by roadsides.

Svetlana picked us up at 10 for our first excursion into the Nature Reserve. In the main street we stopped outside what we had earlier presumed – rightly we now found out – was the ranger station. ‘Our ranger escaped when I went in to collect your lunch, so I have to go and find him again’ Svetlana stated, and to our bemused looks she explained, ‘They are on a fixed wage, and don’t get anything extra for these trips so they are not interested. But we need to have a ranger with us so I have to find him’. She returned soon with a very young man in camouflage military fatigues who sat in the back with us and introduced himself politely but otherwise did not interact with us at all.

We drove across the steppes into the foothills to a smaller ranger station, with an apple orchard planted 30 years earlier. This had an impressive range of apple varieties irrigated by ditches of diverted spring water.

Just beyond this we found ourselves at the edge of a deep, steep canyon. ‘See that green patch over there,’ said Svetlana pointing across the canyon to an area about two thirds of the way up the other side, ‘that is the apple forest we are going to’. A rage of emotions flowed through me – exhilaration and apprehension soon crowded out by concern for Mark’s arthritic knees.

We descended the 300 metres on the

hotter, drier South facing slope – it was probably the worst possible surface for walking on with Mark’s knees (apart from pure mud maybe); steep downhill stretches on lots of rolling, round stones. It was hot and dry with sparse vegetation, the most common trees being junipers with the odd hawthorn. There were some interesting surprises however – for instance an edible allium that grows primarily on hot exposed rocky outcrops (Allium karatavense).

Svetlana was keen to explain the various plants to us. One small purple flowered plant (Ziziphora bungeana) found on the hot southern slope is burned in small stoves, and the soot collected from the smoke on the edges of the vent and used in the production of a fermented milk drink – looking for the black flecks in the drink is an important way to assess if it is homemade! Another plant that looked like an angelica (Atamantha macrophylla) further down towards the creek is used for meat and fish preservation – leaves are wrapped around raw meat to prevent bacterial infection.

I surprised myself with knowing more Latin names than I thought. Often Svetlana did not know the English name for a plant but gave the scientific name which I often recognised to genus level. I think this attests not so much to my good memory, but the fact that so many of these plants are closely related to, or even ancestors of, plants that we have come to live with as humans and these are the sorts of genus names I must have absorbed by osmosis in my permaculture & related reading; I certainly never set out to learn any of them specifically. Three cheers for Linnaeus and his contribution to cross-cultural communication!

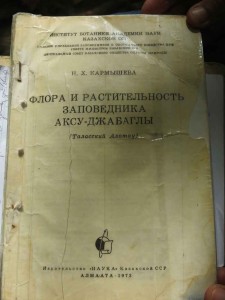

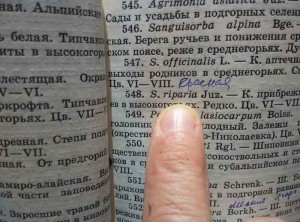

Svetlana was aided by a well-thumbed book of plants: ‘Flora and Vegetation of Aksu-Jabagly Nature Reserve’ 1973. Her copy is missing the cover and is protected with contact on the first and last paper pages, and each individual page has stickytape around the edges to protect it. There are plenty of notes in the margins – a well-loved and useful book. It was written by a woman called Nurania Karmysheva, who was the Park director during the Second World War – it contains 1306 species.

The highlight as we descended the steep dry slope was some dried bear’s poo on the path (yes, the odd things that amuse me…). Bears have been a major influence on apple evolution in the Tian Shan – they prefer the redder, sweeter apples and thus these apples’ seeds are moved around to other areas, and get to start life in a nice nutritious pile of poo. They thus tend to do better than apple seeds that have not been eaten by bears – thus driving apple trees towards redder, sweeter forms. And yes, this dry poo was full of apple seeds – very exciting!

At the bottom of the canyon flowed a swift, cold, turquoise river – a welcome relief from the hot dry slopes above. We drank the water, ate lunch and picked wild raspberries. I appreciated a single wild apple tree with small yellow fruits dropping onto the sandy edge of the river whilst Mark put a cool compress on his knee.

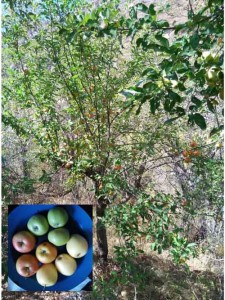

Not far above the river was our first experience of a thicket of wild apples. A red, a yellow and a green apple-bearing tree were all in full fruit. They could easily have been the ancestors of various modern varieties – the green looked like a small Granny Smith, the yellow like a Golden Delicious and the red like a dull Jonathan. They were all quite eatable too – the red one was especially delicious. It was quite a thrilling and emotional moment to be under these trees and feel that I was surrounded by ancient apple genetics.

The main apple forest was further up however, and we kept moving. Although going uphill, it was now milder, greener and shadier than it had been on our descent due to the north-facing slope.

We finally reached a quite dense patch of mostly apple trees, rather crowded with multiple branches and casting good shade. There were also what Svetlana called Mahaleb cherries (Padus mahaleb) – these were common trees that occur singularly (albeit with multiple suckers) and as a regular companion to the apples.

We finally reached a quite dense patch of mostly apple trees, rather crowded with multiple branches and casting good shade. There were also what Svetlana called Mahaleb cherries (Padus mahaleb) – these were common trees that occur singularly (albeit with multiple suckers) and as a regular companion to the apples.

There was less diversity in the apples than I expected. All the trees were fairly similar and not too different from what one would recognise as an apple tree. The mature trees were around 6 – 8 metres high, multi-branched and spreading. The apples were various shapes and sizes (with small yellow round ones being the must common) but none of the tastes were anything I hadn’t tasted before in an apple – many were quite sour, bitter, floury and/or astringent but nothing unexpected. The only exception to this was the single apple tree down by the river, which had a slight resinous taste I had never encountered.

It was interesting that the apple forests were in smaller pockets than I had envisioned – I had expected widespread forests but in the Aksu-Jambagly Nature Reserve apple groves tended to occur in only valleys or gullies sheltered from the hot drying sun. (Although historically there were far more widespread areas of apple forest in these mountains, particularly near Almaty).

It was an exhilarating day. And yes, we even made it up and back out of the canyon.